Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart is the most iconic classical composer of all time. It’s a status not just drawn from the fact that he’s behind some of the most recognizable pieces of music ever written, but also because of the prodigious nature of where these works came from.

We’ve all heard the stories; he started composing at around the age of four, he completed his first symphony by age eight, and so on. But his savant-like ear for music also led to controversy, such as that one time he essentially pirated music from the Pope.

Miserere – the Cause for this Misery

A little background. A pontiff didn’t write the pirated piece. Rather, Pope Urban VIII commissioned Italian composer and Catholic priest Gregorio Allegri to write a hymn for Holy Week back around 1638.

Allegri responded by writing Miserere mei Deus (translation: “Have mercy on me, O God”); a piece of music based on Psalm 51. Commonly known as Miserere, it was the last of a dozen different settings of the same text that was written for the Vatican over a 120-year stretch.

Miserere was also the most popular. So much so, it was treated with near sacred reverence by the Catholic Church. So sacred, in fact, that the Pope forbade anyone from trying to transcribe the piece. This was no idle decree, either – he threatened excommunication to those that dare go rogue against his proclamation.

This didn’t mean there weren’t copies made. There was a transcription designed for the Holy Roman Emperor Leopold I, the King of Portugal, and composer/Catholic friar Giovanni Battista Martini. These copies aren’t even without their own controversy.

According to legend, Leopold arranged for a performance of his transcribed copy put forth by the finest singers at his disposal. He found the performance to be so dull, he let the Pope know he felt he had been cheated out of the right copy. This upset the Pope so much, he fired the Maestro di Cappella, the man that provided Leopold with the sheet music.

It turns out that Leopold, in fact, had the right copy – it’s just that the Papal Choir had made so many improvised, unnoted embellishments to the piece, it changed the piece fundamentally. Once this was discovered, the Maestro supposedly got his job back.

While this anecdote touches on one of but a trio of copies that were transcribed, it should be noted that the piece was otherwise kept under wraps by the Catholic Church for the next 140 years or so, threat of excommunication still firmly in place.

Enter, Stage Left: Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart enters the scene.

Amadeus Gets His Prodigious Freak On

The year: 1770. Mozart was just 14 years old at the time.

He’d already made a name for himself even at this early age, traveling Europe and performing for royalty at the Imperial Courts of Vienna and Prague. He was in the midst of touring Italy with his father. They arrived in Rome in the middle of Holy Week, and Mozart attended the Holy Wednesday Tenebrae service.

It was there that Mozart heard the Miserere in full, in the manner that Allegri had intended: Two choirs; one choir singing a basic chant; a second choir vocalizing the elaboration.

The piece impressed Mozart so much, he returned home and did what any 14-year-old genius childhood prodigy would do: He transcribed the piece totally from memory. Mozart must have known that what he wrote down wasn’t completely accurate, either…

He returned to the Sistine Chapel on Good Friday, where the Miserere was performed again. He then went home and corrected whatever errors to his written transcript. There is a legend that he actually snuck the piece into the church under his hat and made the corrections on the spot, but this legend seems rooted in myth.

Adding to the story’s mythos is that Mozart’s transcription was not necessarily lifted directly from Allegri’s version. Mozart was supposedly able to decipher and notate the various embellishments that the Papal Choir added to the performance. Unfortunately, this part of the story seems destined to remain murky – Mozart’s original copy has been lost to history.

A Little Too Much Fame for Mozart

The immediate journey of Mozart’s Miserere from initial transcription to published work is a touch murky. The most common narrative is that the Mozart family encountered British music historian Dr. Charles Burney shortly thereafter, and either sold it to him or gave it to him outright.

Burney took it to back to London and published the piece in 1771. Eventually, the piece generated interest and increased fame for the teenager around the world.

Ultimately, the reach of the piece’s scope made it back to Rome. It caught the ear of Pope Clement XIV, who was filling the seat of the Papacy at the time. Clement got his hands on one of these unauthorized copies of Miserere and saw that it was allegedly extremely accurate.

Exactly how he received this document is up for debate. However, most historians believe that it came directly from Mozart’s father, Leopold Mozart. Based on letters recently released by the Vatican archives, it’s noted that the Pope was made aware of what Mozart had done via an anonymous individual that had “petitioned his name.”

Even though there is no moniker associated with this letter, given that Mozart’s dad had a reputation for bragging about his son’s genius, it is speculated that he couldn’t keep his fatherly pride to himself and wrote to the Vatican to spill the beans.

Regardless of how the Pope received the note, one thing’s for certain: Mozart had broken a Papal mandate that had been on the books for nearly a century and a half. The potential for deep trouble was on the table. Remember, this was an excommunication-worthy offense.

Fortunately for Mozart, cooler heads prevailed. The Pope was blown away by the prodigy’s handiwork, and summoned him to Rome not to get booted from the Church, but embrace his talent and his musical ambition. He was so impressed, in fact, he awarded Mozart with the chivalric Order of the Golden Spur; a bit of hardware that can best be described as a Papal knighthood.

The fact that the Pope was enraptured by the piece on the level that he was lends a ton of credence to the notion that whatever Mozart wrote, it was spot-on.

The gravitas of the Papal audience and the subsequent praise was not something lost on Mozart at all. For a stretch, he was extremely proud of this accomplishment. It’s said that he wore the cross medal bestowed upon him by the Pope constantly and that he developed a habit of signing his name as “Chevalier de Mozart.”

Unfortunately, this all ceased around the time he was 21. It was revealed by his father in a letter dated October of 1777 that Mozart got mocked by various nobles for wearing the cross during a concert. This incident led him to apparently stop wearing the medal. He also reverted to signing his name without the Chevalier title, as well.

Peer pressure is apparently not a new problem.

The Aftermath: Mozart’s Miserere Ripple Effect

Mozart’s interpretation of Miserere had a ripple effect beyond the composer’s life. The ban on copying the piece was lifted by Pope Clement XIV, an act that made the piece of music readily accessible to the masses.

With that being said, it did take a little time for a genuine Vatican version of the song could be enjoyed outside the Vatican. The Vatican-embellished take on the song wasn’t published until a Catholic priest named Pietro Alfieri did so in 1840.

Oddly enough, even as that song got published to the masses, it’s not the version of Miserere that we’re familiar with today. In fact, there’s a strong case that the great composer Felix Mendelssohn deserves a co-writing credit. It’s a credit whose status was brought about completely by accident.

IN 1831, Mendelssohn decided to make his own transcription of the piece transposed up a notch or two, but not on purpose. The version he was basing his transcription on was sung higher than originally intended. Mendelssohn’s version may have been confined to relative obscurity if not for a publication gaffe that came about some 50 years later.

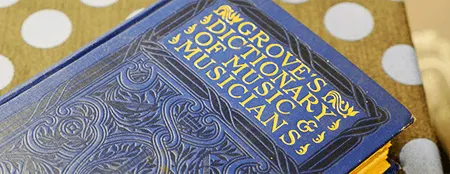

When the first edition of Grove’s Dictionary of Music and Musicians (now Grove Music Online) was being assembled in 1880, a small snippet of Mendelssohn’s version of Miserere was erroneously inserted into a passage that was being used to illustrate an article.

This error took on a life of its own, as it was reproduced in so many versions, it was essentially accepted as canon. Interestingly enough, Mendelssohn’s small section has gone on to be what many consider to be the most iconic passage of the entire piece.

So the next time you hear Miserere, whether it be at a Holy Week service or on the local classic radio station, take a moment to appreciate the near Frankenstein-nature of this song. Ponder how this was a song forbidden by the Pope to be replicated.

Think about how Mozart’s “pirated” and embellished version of such musical forbidden fruit was awarded handsomely by a different Holy Father. And remember how the version we hear today had an accidental assist from Felix Mendelssohn.

Song histories simply don’t get much cooler than this.