Most of us in the recording industry have a solid understanding of how compressors work. We know how to tweak the settings to achieve our goals in a mix.

But even the most well-informed of us are hanging on to some misconceptions about the technical aspects of how these crazy machines function.

Let’s start with the most simple myths and misguidance that’s out there and move to increasingly complex concepts. There’s something in here for everyone. A full understanding of these myths will improve your mixing and mastering.

You’ll add a few techniques to your process and correct some harmful ones… each incrementally improving your mixes until your competitors are sending spies to your studio to figure out exactly what gear you’re using and how you’re using it.

Take your time to consider each point. They are so ingrained in our minds that it’s easy to gloss over it and dismiss it, but what you’ll find here is nothing but the truth behind the veil! Your art and your income are going to jump to the next level with the debunking of these compression myths below.

1) Compressors Increase Your Volume

Verdict: Completely False

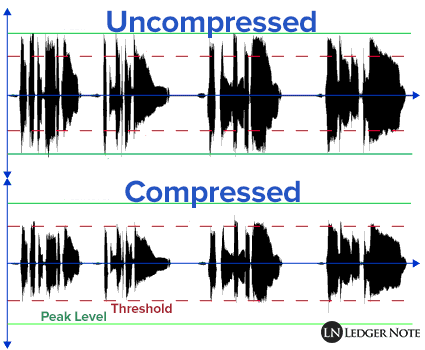

It might seem this way but the truth is the exact opposite! You’re setting your threshold and compression ratio and suddenly all of the quiet parts sound louder.

The low volume parts may sound louder in relation to the previous parts with higher amplitude, but if all other variables are held the same, what you’ve done is turn down the volume on the highest amplitude portions of the track.

The resulting volume on that track and the song overall will decrease, although the root mean square (kind of like an average) volume may have increased, effecting your perception of overall loudness.

The only time this myth becomes true is after you’ve adjusted your makeup gain to compensate for the fact that you’ve actually just made the loud parts less loud. In case you don’t know, gain is the ratio of the output volume to the input volume.

You’d turn that up to “make up” for the difference in volume you lost when compressing. Think about it… it’s called a compressor for a reason.

There is the caveat of what is called an expander, which others call upward compression, that increases the volume underneath the threshold, but most don’t categorize these as a compressor type, just a similar tool.

2) They Replace the Need for Volume Automation

Verdict: Absolutely False

No! It’s true that compressors automatically ride the gain in a fashion to reduce the variation in dynamics between quiet and loud parts.

But if you’re smashing your volume to reduce this dynamic range so that you can choose a single volume setting for your entire mix, you’re losing a lot of opportunity to breathe life into your mix.

Some syllables in your vocals might need a slight boost even after compression to be more intelligible. You might need to increase the volume of your guitars as your song transitions into the chorus and more elements are added to the mix.

Don’t create dead, lifeless, robotic mixes! Take advantage of every tool you have (and need).

The paragraph above explains why you’d still use automation after compressing, but volume automation is relevant before compression as well.

If you have a track that varies in volume too much, such as a vocalist that moves further and closer from the microphone or turns their head frequently to read lyrics, you’ll need to fix that variation first before you compress.

If you attempt to do this solely with a compressor you’ll end up with severely squashed parts and parts that aren’t squashed enough. Volume automation is the tool designed to solve this problem.

3) All Compressors Sound the Same & Do the Same Thing

Verdict: 70% False

Yes, they all do the same thing, which is taming your audio signals dynamic range. But how they do it is not remotely the same. The fact that you see professionals arguing over which is the best vocal compressor constantly should clue you in.

And lets not forget about multiband compressors, which do the “same thing” but only to specific frequency ranges. And there are some like the FMR RNC that even have serialized compression in them.

The reality is hardware compressors have different electronics inside of them. Some are solid-state. Some are solid-state with transformers that add a warm saturation to your signal. Some have vacuum tubes that add harmonic distortion. Some are limiting amplifiers.

Then you move over to software compressors. Each of these plugins uses different algorithms to emulate different hardware circuitry.

The default Logic Pro compressor offers you six different models to use, including VCA, FET, and Opto compressors. Why would they even bother if they all sound the same?

The problem is that amateurs can’t hear the difference or don’t bother to listen for the difference, and the myth continues to get perpetuated. A lot of this has to do with simply not being exposed to quality compressors and only hearing cheap ones.

4) You Can Set & Forget Your Attack & Release Controls

Verdict: Not If You Want Good Results

I mean… sure, you can do that. You can try to simplify your life by giving up 50% of your compressors ability to sculpt your sound. So many beginners will set their attack and release to the fastest settings and go from there. They give up the ability to sculpt or even allow initial transients to exist.

They can’t figure out why their sustained bass notes feel like they are wobbling and pumping on the tail ends of the sounds and sound lifeless when they first hit. Attack and release give you complete control over these problems if you bother to understand how to use them. It’s not even hard.

Don’t forfeit half of the parameters available to you out of laziness. Not every source needs to be treated the same, especially when the lengths of notes vary so drastically and their initial attacks play such a huge role in defining how they’re perceived by the human ear.

5) Sidechain Compression is Cheating & Cheap

Verdict: Moronic & Self-Destructive

Who comes up with this crap? “If you can’t fix it in the mix then it’s a problem with your orchestration and arrangement.” No.

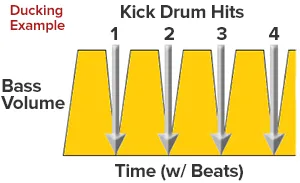

For instance, take a kick drum and bass guitar. You might meticulously choose ones that have their fundamentals or harmonics in slightly different ranges, but “slightly” only helps so much.

And there’s no reason to use an EQ to destroy your bass tone throughout the entire song just so those relatively few moments when the kick fires sound better.

Sidechaining, in this case, is telling the compressor to fire on the bass only when the kick drum triggers it, as seen in the image below. It causes the bass to “duck” out of the way of the kick drum so it can be heard clearly, saving you from unneccesarily equalizing the bass.

Sidechain compression is absolutely not cheating or cheap. It’s an advanced technique. The same people who say this are happy to line up a de-esser to fix problems in the vocals, which is essentially the same concept using a single-band compressor.

Ducking your bass when your kick hits isn’t cheap, it’s smart. Turning mixing into a purist or morality issue is silly. The only thing that matters is the end result.

6) A Limiter is Enough When Mastering

Verdict: No. Please, No.

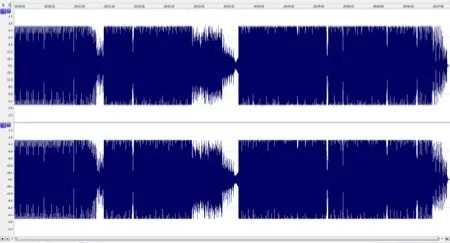

There’s nothing worse than amateur mastering (and it doesn’t even deserve THAT label). A hobbyist will have created his best mix and then want to increase the overall volume of the track to match those of professional releases before he slings it all over the internet.

So he slaps a limiter on his master output and pushes up the volume, letting the peaks literally get chopped off so the average volume is increased.

People literally agonize over every detail of their mix and gain staging to make sure there’s no clipping, and then clip off 50% of their dynamics during their “mastering” phase. Sure, use a limiter, but first make sure you’re compressing in the mix as much as you need and then apply additional compression during the mastering stage.

If you can gain an additional 2dB of average volume with small 2:1 ratio and a high threshold, why wouldn’t you do that instead of clipping off the tops of your waveforms? Always achieve your volume gains musically first!

You should treat a limiter as nothing more than a safety net to stop you from clipping, preferably during tracking and not during mixing or mastering. A compressor should come before the limiter, in my opinion, which leads us to the next myth.

7) Compression Starts When The Threshold is Crossed

Verdict: It Depends on the Knee

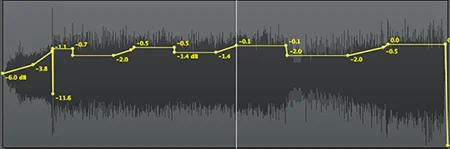

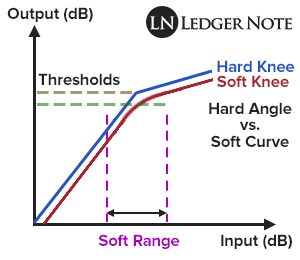

Another feature that many don’t configure is the knee of the ratio. You have two options: a hard knee and a soft knee. A hard knee works as you would expect. The compression begins clamping down as soon as the amplitude of the wave crosses the threshold value.

But a soft knee creates a range of values, a plus-or-minus, of decibels around the threshold that directs the compression to start. Let’s say that value is a plus-or-minus 3 dB and the threshold is set to -25 dB with a ratio of 5:1.

At -28 dB in volume (minus 3), the ratio may kick in at 3:1, then at -25 dB the ratio hits at 4:1. It’s only when you hit -22 dB (plus 3) that the full ratio of 5:1 kicks in. This gives a “softer,” more rounded, and more musical sound than a hard knee does.

This is a good place to mention that the threshold doesn’t always deal with the peaks of the waveform. If you place your device in Peak Mode, then yes, it does.

But if you place it in RMS Mode (meaning root mean square, a more mathematically advanced ‘average’) it will calculate that value and switch the threshold over to RMS as well.

8) Never Track Through a Compressor

Verdict: I Say The Opposite

Absolutes like “never” and “always” are attempts at shortcuts that always result in lesser results. This advice comes from the “always record dry” crowd.

That makes sense in the digital age and I understand why people say it. If you add EQ or reverb before the converters, then you can’t undo it. You’re stuck with that choice. But it’s not always an “on or off” scenario when it comes to compression.

Imagine that you’re recording an extremely dynamic rock singer. He gets excited and delivers the world’s most perfect and emotional performance ever, but unfortunately he got too loud and some parts were distorted.

You could have saved this from happening by using a small amount of compression while tracking. Nobody said you have to completely crush the dynamics during tracking.

You can use it as a safety measure for when a vocalist wavers too close to the mic, for instance. With a high enough threshold it won’t even trigger most of the time. You can compress vocals on the way in slightly and then again later in the mix.

And if you choose a nice hardware compressor with great coloration, you can impart that onto the track as well.

9) Always Equalize Before Compressing

Verdict: Depends on When…

People sling this one out there as a truth you should never stray from. But they never stop to consider what stage of production you’re in. Are you recording, mixing, or mastering? That will make all of the difference.

For instance, during recording, as mentioned in the section above, you often want to compress just to save yourself from possibly clipping. There’s no need to set up an EQ here first.

But when mixing, it generally makes sense to equalize first because you don’t want frequencies that won’t even end up in the track being the ones triggering the compressor. That will upset your frequency balance even more, making you need to EQ before and after, which is typically unnecessary.

But then you think about mastering, where all types of compression and EQ have already been put in place, whether on individual tracks or on the master outputs (2-bus, summing outputs, etc.) to bring some glue to the song.

If this myth is true then mastering wouldn’t and couldn’t exist, because there’s always more compression in the final mastering phase of production.

The only time you should accept the word “always” is if someone says to always watch out for times when people say always.

10) Attack & Release Tell The Compressor When to Start or Stop

Verdict: A Semi-True Simplification

This isn’t true, although I’m pretty sure I’ve typed this exact thing on this very site before. It’s the easy way to understand it. What the attack setting is actually doing is setting up the time it takes for the compression to ramp up to 2/3rd’s of the compression ratio you’ve designated.

So while it’s definitely a sort of delay to full compression, it’s not a delay to starting the compression. It has started and almost reaches your designated ratio in the number of milliseconds you set up. The inverse is true for the release.

I should place a disclaimer here or I’m perpetuating another myth. The 2/3rd’s value is an average estimate. There’s no actual standardized value here so every compressor might vary a bit from that number.

But that number is far closer to an absolute truth than believing that there’s a complete delay to starting or stopping. As soon as your signal crosses the threshold, the process begins regardless.

We should also mention that the attacking and releasing don’t only occur above and below the threshold, respectively.

Attack occurs when the gain meter is increasing (gain being reduced) and release occurs when the gain meter is decreasing (gain allowed to increase, even if an overall reduction is still happening). That means release can happen above the threshold too.

Bonus Myth: Multiband Compressors are Stupid & Complicated

Verdict: Half False & Half True

They are definitely complicated but nowhere near stupid. Don’t dismiss the power of multiband compression just because it takes a little more time (and a lot more attention).

This especially goes out to anyone learning and practicing mastering. A common problem is to wrap up your album or mix and think it’s all good. You don’t even bother archiving your source material because your mixes are so good.

Then you start hearing your songs together, one after another, and realize they don’t have the same tonal and sonic footprints that make them feel like a uniform work of art. They sound like 15 songs recorded in different places and at different times, slapped together and called an album.

Is it too late? Not by a long shot if you’re willing to use a multiband compressor. You can reduce the volume of the bass frequencies as a whole with EQ, but you can’t shape the peaks or allow transients to pop through with an equalizer. This is why you see some re-masters of classic releases coming out.

It’s never too late to fix up cruddy mixes, but you need the right tools and this is the precision scalpel. You can massage each song individually, for instance, to fix uncontrolled vocals in one song and booming bass in the next.

Bonus Myth: Compressors Create Thicker, Fatter, Rounder Sounds

Verdict: Nope, You Can Make Thin Sounds Too

First of all, those are very subjective words that some people repeat and don’t even understand what they mean. This is generally referring to a more pronounced, warmer, controlled bass region. And a compressor doesn’t always achieve this.

Think of a synthesizer bass line with tons of distortion so the harmonics can pop out in the mix and make it easier to hear. You may slap a compressor on the track and set a threshold that enhances your harmonics. Too deep of a threshold removes them too much.

So what you’re doing is sculpting mid and high frequency sounds and never touching the bass portions. They never get sculpted into a rounder, smoother, thicker, fatter sound.

Now, you could send a copy of the track to a bus and EQ out the bass so you’re left with the mid and high frequencies.

Then on the original track you can EQ out the mids and highs so you’re left with the bass, then compress the lowest frequencies with a low threshold and low ratio to even things out, and rebalance the volumes on the faders.

Now you have a fatter bass. But you can achieve the opposite as well if you so choose. It all depends on how you use it. It’s like using the backside of a hammer to pound nails.

Sure, you’ve got the right tool for the job but you’re using it completely wrong. How much does this myth change when you’re talking about serial compression or parallel compression too? This is why you can’t buy into these binary myths!

The Compression Truth Will Set You Free

There’s a good chunk of mixing and mastering knowledge wrapped up in trying to unravel these misunderstandings surrounding compressors. There’s a handful of shortcuts you can stop using and a boatload of techniques you should start using, despite some prevalent misguidance out there.

These myths are out there because a lot of people are lazy, the topic is complex, and most importantly because some folks don’t want their competitors to get the upper hand…

Use the tools at your disposal properly and effectively to cater to yourself, your clients, and your listeners. If someone doesn’t fall in those categories, then their opinions don’t matter!