It’s easy to run into musical modes and think, “What the heck is going on? Why does all of this need to be so convoluted and complicated?”

It does seem that way at first until you work with modes enough to spot the pattern. Then not only does it click into place but you can even work your way through it in your head! The pattern makes it extremely simple to follow…

And that’s what we’re here to show you today. You have experience with scales and chords at this point and maybe even have gone on the Circle of Fifths journey (another pattern you should know).

We’ll do a quick overview of scales and how they are built so we can lead right into modes, which are only slight variations of scales! If you think of it in this manner, then it makes plenty of sense.

For some odd reason everyone likes to explain modes based on the number of half-steps between notes, but who can sit there and count semitones when the band calls out a certain song in a certain key and mode? Nobody, and that’s not how they think about it either.

There’s no reason to make this harder than it has to be, so forget the rest and get ready for the best explanation you’ll find about musical modes.

We’re all used to the major and minor scales as listeners, songwriters, and music theorists… even to the point of boredom.

They are so common and conventional that they hardly inspire us even with the most unique chord progressions. This has happened because not enough people understand modes well enough for them to be used widely!

Modern modes are built on the major scale with one fundamental difference that makes them a renewed sense of freshness…

There are lots of other types of modes you don’t need to worry about just yet. With our simple explanation you can capture your listener’s imagination and intrigue easily with the modern Western kind.

The hardest part is remembering the names of the modes! But we’ll get to that in a second. First the basic building blocks need to be laid out.

The Major Scale: The Basis for Explaining Musical Modes

Let me preface by saying that, yes, minor scales also have modes but they behave the same as the ones based on the major scale, which is vastly easier to understand especially when C-Major is used as the example (which we will be doing).

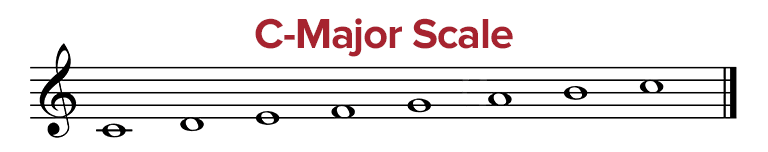

Every scale is made up of seven notes that start from the tonic and climb upward. When you hit the eighth scale degree you’re back to the tonic and have climbed on octave. All Western scales and modes are all built from the white-key only diatonic scale of six perfect fifths (also known as C-Major).

The type of scale or mode is determined by the sequence of intervals between the notes in the scale.

In the case of a major scale, you begin at the tonic and proceed as follows:

W – W – H – W – W – W – H

The letters refer to either whole steps (or tones) and half-steps (or semitones). So with C-Major, which includes no flats or sharps, it looks like this:

As you can see, things are very simple in C-Major with a tonic of C and no accents. Let’s build the modes off of C-Major first to wrap our heads around the process.

Constructing the Musical Modes

Now remember, we are working in the major scale with C-Major.

There are seven modes available to you in modern Western music. Why seven? Because each mode is based on each note of a scale as the new tonic! That will make sense in just one second. Here are your seven basic modes:

- Ionian – C

- Dorian – D

- Phrygian – E

- Lydian – F

- Mixolydian – G

- Aeolian – A

- Locrian – B

They are numbered 1 through 7, and their number is the scale degree which acts as their new tonic.

So for instance, the Dorian mode of C-Major begins on the 2nd scale degree, D, and then climbs through to C at the 7th scale degree, using the exact same pitches with no sharps or flats.

The Lydian mode of C-Major begins on the 4th scale degree, F, and climbs on to E at the 7th degree. You simply shift yourself forward a number of scale degrees and use that note as your new tonic.

That is how it’s done, but the problem is that you won’t be communicating about it in this way. The reason is that musicians talk to each other about scales based on the tonic, or root note.

So you wouldn’t say “We’re going to play this one in the Dorian mode based on C-Major.” You’ll actually say “We’ll be playing this tune in D-Dorian,” because the tonic is the D note.

What’s happening is that after you shift forward on the scale degrees to find your new tonic, you’re also shifting the sequence of intervals away from the major scale sequence of W – W – H – W – W – W – H.

While modes are easily constructed from C-Major, what truly defines them is their sequence of intervals, which makes them very different from your typical scales and key signatures.

All major scales follow the above sequence which leads the various accents used in different major key signatures. But modes wrap through that sequence instead.

Let’s look at our list again in light of this new information in table format:

| Mode | Interval Sequence | |||||||

| Ionian | W | W | H | W | W | W | H | |

| Dorian | W | H | W | W | W | H | W | |

| Phrygian | H | W | W | W | H | W | W | |

| Lydian | W | W | W | H | W | W | H | |

| Mixolydian | W | W | H | W | W | H | W | |

| Aeolian | W | H | W | W | H | W | W | |

| Locrian | H | W | W | H | W | W | W | |

Visually you can see the pattern rolling out with the diagonals full of H’s. This is how you’ll remember which mode features which sequence of intervals until you begin to have it memorized.

Ultimately you’ll want to think about it in terms of scale degrees and accents, because you can apply these modes to any major or minor scale.

Because a mode is a type of variation on a scale, there are no key signatures to memorize. What you need to remember is how you will alter the existing key signature.

This final table represents how you should think about these modes once you’re able to work out the details in your head. Understanding is the most important, and then you won’t have to bother with committing it to memory. It will happen naturally.

| Mode | Interval Sequence | |||||||

| Ionian | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

| Dorian | 1 | 2 | b3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | b7 | |

| Phrygian | 1 | b2 | b3 | 4 | 5 | b6 | b7 | |

| Lydian | 1 | 2 | 3 | #4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

| Mixolydian | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | b7 | |

| Aeolian | 1 | 2 | b3 | 4 | 5 | b6 | b7 | |

| Locrian | 1 | b2 | b3 | 4 | b5 | b6 | b7 | |

If you’re the type with a strong imagery-based memory then you’ll have an easy time with this, because there’s even a visual pattern in this layout.

The real absurdity comes when you realize that some of these are the exact same scales by different names. For instance, all of these are the same:

- C Lydian

- D Mixolydian

- E Aeolian

- F# Locrian

- G Ionian

- A Dorian

- B Phrygian

It can get a little silly like that, but fortunately you’ll be working off of chord charts or at least working on a staff. Only the super modal jazz guys improvise while jumping around modes and keys.

Now, we’ll talk about each mode itself and the peculiarities of each. Each has a specific note that gives it it’s characteristic. Each is also major or minor in it’s own right beyond the scale you start with, which will help you choose which to use to match the emotional impact of your song.

Musical Modes’ Characteristics

Each of the main seven modes of Western music has certain characteristics that can help you achieve your songwriting goals. Let’s look at each individually.

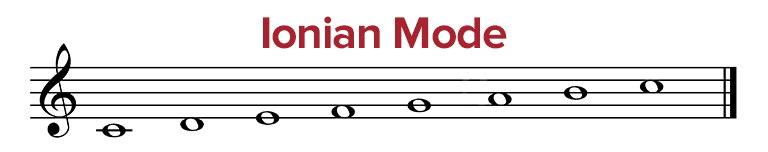

Ionian Mode

- Characteristic Degree: N/A

- Interval Sequence: W-W-H-W-W-W-H

- Example: Let It Be by The Beatles

- Example: Goodbye to Romance by Ozzy Osbourne

An astute observer will have noticed that the Ionian mode is none other than the Major Scale by another name. It is the exact same. This is the mode we all know and love, used in pop music non-stop (most of the time with the same chord progression too).

The attractive aspect of this mode, other than it being the easiest to work with as it demands no variations on the chosen scale, is the tension and release that comes out of the half step between the 6th and 7th scale degrees.

The tension is released as the 7th resolves back to the root, creating very clearly delineated melody loops and song segments.

The Ionian mode produces an uplifting, innocent, happy, and upbeat style of song. You hear it in pop music, children’s music, and gospel.

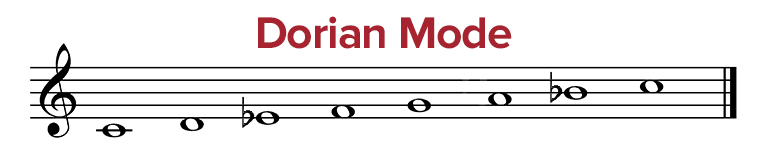

Dorian Mode

- Characteristic Degree: 6

- Interval Sequence: W-H-W-W-W-H-W

- Example: Scarborough Fair by Simon & Garfunkel

- Example: A Horse With No Name by America

The Dorian mode feels like a Minor Scale due to the minor triad up front, but here the 6th scale degree is natural instead of flat while the 7th is flat.

This gives this mode two curious characteristics. It sounds melancholic but brighter and more positive than the typical minor scale. The 7th doesn’t quite resolve which creates a sense of restlessness.

You hear this mode used in lots of Celtic and Irish music and those genres heavily influenced by them like Folk, Country, Blues, and Bluegrass. More examples are Chris Isaak’s Wicked Game, Daft Punk’s Get Lucky, and Tears for Fears’ Mad World.

Phrygian Mode

- Characteristic Degree: b2

- Interval Sequence: H-W-W-W-H-W-W

- Example: Knight Rider Theme by Stu Phillips

- Example: White Rabbit by Jefferson Airplane

The Phrygian mode creates an ambiguous sound that leaves the listener uncertain of what they are hearing. Because the 2nd note is flat, it sounds strange to most people who are used to a whole step to the 2nd degree as in typical major and minor scales in the Ionian mode.

Because of this, it’s not used in music so much as in film scores. This strangeness can create a sense of mystery, dread, tension, and an impending negative event while still having a sense of warmth. You’ll catch some classical artists using it as well as metal bands. It’s also known as the Spanish Gypsy Scale.

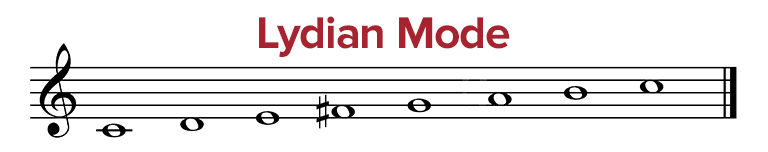

Lydian Mode

- Characteristic Degree: #4

- Interval Sequence: W-W-W-H-W-W-H

- Example: The Simpson’s Theme by Danny Elfman

- Example: The Jetson’s Theme by Hoyt Curtin

The Lydian mode is similar to Ionian in the sense that it first chord is still a major triad but the intervals are unexpected and surprising. They vary by one note, the sharp fourth. It largely shares the same sounds and uses as Ionian for happy, pop, and children’s music.

The sharp fourth strongly wants to resolve to the 5th and it’s important that you use this to your advantage or you might as well just be writing in a major scale. The Jazz genre and many show-tunes have exploited this very well to keep you engaged in the performances.

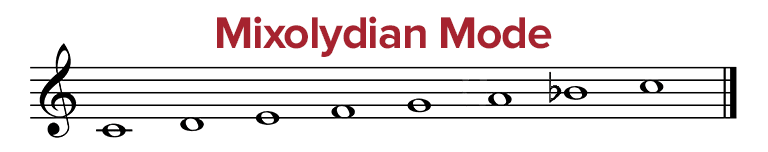

Mixolydian Mode

- Characteristic Degree: b7

- Interval Sequence: W-W-H-W-W-H-W

- Example: Norwegian Wood by The Beatles

- Example: Sweet Home Alabama by Lynyrd Skynyrd

The Mixolydian mode also varies from Ionian on one single note, the flattened 7th. It’s a popular choice for solo improvisations when in a major key because it provides a slightly unfamiliar counterpoint to help keep things fresh.

You hear this a lot in rock and country songs in major scales, especially in solos and bridges. It can provide a smoother, less innocent sound to otherwise happy songs. It provides the same sense of not resolving like Dorian does if exploited.

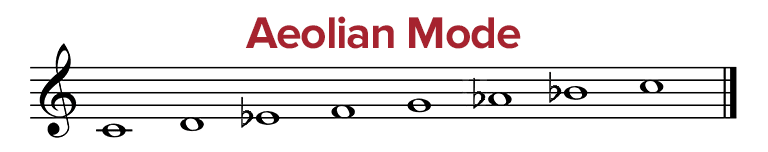

Aeolian Mode

- Characteristic Degree: b6

- Interval Sequence: W-H-W-W-H-W-W

- Example: Losing My Religion by REM

- Example: I Kissed a Girl by Katy Perry

The Aeolian mode is the Natural Minor Scale. It provides the modern blues sound of sadness, regret, resentment, and despair. Lots of Rock music has drawn upon this sound as well due to its relation to the minor pentatonic scale.

It gives a slight sense of the Renaissance era at times due to the 6th and 7th scale degrees being flattened instead of natural. There are no lack of examples for the Aeolian mode as it appears in hundreds of thousands of minor key songs.

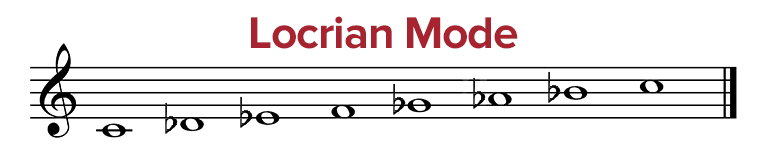

Locrian Mode

- Characteristic Degree: b5

- Interval Sequence: H-W-W-H-W-W-W

- Example: Ride the Lightning by Metallica

- Example: Army of Me by Björk

The Locrian mode stands out due to its flat fifth pitch, giving it its characteristic darkness. Because so much Western music depends on the major I and major V chords, you don’t hear Locrian that much due to the diminished V chord.

Many Western composers have gone as far as to categorize this mode as theoretical with no practical application.

This is a very dark sound with a sense of brooding anger and sadness together. Heavy metal artists will use it occasionally along with classical composers looking for something much darker and dissident than other modes provide.

That’s Music Modes Explained!

The bottom line is that millions of musicians do just fine never touching the seven modes.

You can get away with it too, but if you want to open up an entire extra avenue to help propel your music into uniqueness then you should take the time to learn how the modes are built and how to construct them on whatever scale you’re using.

It’s easy enough now that you’ve had the Ledger Note treatment of the Musical Modes Explained!