Today we’re going back, way back, all the way to 1954. While the exact year is fuzzy, we accept that as the year that the Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA) established the RIAA curve standardization for records and record players.

This article starts as a history lesson that merges into an explanation of why this RIAA equalization still matters today. It’s interesting to think about but one of the largest money-making genres in the music industry still uses turntables daily.

Without knowledge of this RIAA filter, things get whacky fast. It’s easy to hear what’s going on but it’s even easier to think there’s a problem in your gear (if you aren’t using professional equipment). In some cases you’ll continue working and never notice the problem. There’s a reason for that, too.

Let’s jump into it. If you’re a rap beat producer, you especially need to read through this. It’s extremely relevant and of importance to anyone that samples from records, creates remixes of old recordings, or just has an interest in the history of the studio recording industry.

What is the RIAA Curve?

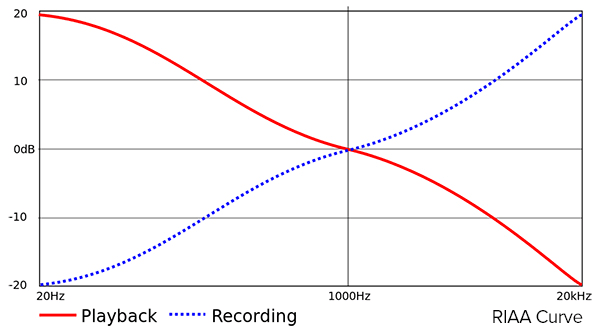

The RIAA curve is an equalization filter applied to vinyl records and then corrected in record player amplifiers in such a way that the listener is never aware that any change has occurred.

On the record itself, songs are engraved so that low frequencies are cut in volume while high frequencies are boosted. In the record player’s amplification stage, low frequencies are boosted and high frequencies are cut in the exact same amounts.

The Benefits & Problems of the RIAA Curve

This inverse filter cancels out the initial curve, but provides several benefits that outweigh the problems it introduces:

- It allows for more time per side of the vinyl record.

- It reduces typical noise like hiss and clicks associated with records.

- It boosts the rumble caused by the turntable’s drive mechanism.

Let’s look at each of these points to understand why this filter was ever applied in the first place. The two benefits outweigh the problem introduced which was later corrected by turntable manufacturers anyways.

Why the Curve Lowers Bass Volume

On a vinyl record recordings are engraved into grooves that spiral inward to the center of the platter. The louder the bass frequencies are, the wider these grooves have to be. So by using the curve to reduce the volume of the low-end frequencies, these grooves could be less wide.

This allowed for more time to be packed onto each record. The standard vinyl record is a 12 inches in diameter and spins at 33 revolutions per minute (RPM). Thanks to the RIAA curve we were able to increase the amount of time per side to 22 minutes.

Why the Curve Raises High Frequency Volumes

Records and record player needles are sensitive, so much that even the slightest amount of dust and hair accumulated on either will cause high frequency hiss sounds and the occasional popping sound. By boosting high frequency volumes, this also increases the volume of these hisses and crackles. So why do it?

Because when you later invert the RIAA equalization curve in the electronics of the turntable, you end up reducing the volume of these noises, providing an even clearer listening experience. Let me make more sense of this for you.

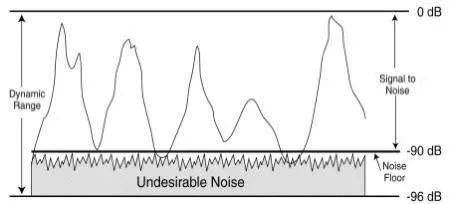

No matter what audio is being played by the needle, the hiss and clicks will be the same volume. So by boosting the high frequencies on the record itself, they will drown out these noises. This increases the signal-to-noise ratio, which reduces the volume of the noise floor.

So during playback, when the high frequencies are then lowered back to their correct volumes, the noises (which were also boosted but not as much relative to the actual music) are reduced in volume lower than they would have been played back without this equalization curve being applied.

The Problem & Solution of the Turntable Rumble

Unfortunately, the exact opposite occurs for low frequency noise. Because the source material (the music engraved on the record) has its bass frequencies reduced and then boosted, this increases the volume of the turntable’s drive mechanism.

The drive mechanism vibrates at a low frequency rate which can be heard during audio playback. The solution was simple: turntable manufacturers were forced to use tighter tolerances and better construction to reduce the vibrations created by the drive mechanism.

So in the end, not only did we get higher quality audio from records, but we were offered higher quality record players in the process as the manufacturers competed to have the quietest drive mechanisms. You can’t beat that as a consumer!

The Quick History of RIAA Equalization

As early as 1926, Bell Telephone Laboratories had to boost highs and attenuate bass to compensate for the recording pattern of the Western Electric rubber line magnetic disc cutter, due to its constant velocity groove cutting. This meant high frequencies would playback too quietly while bass would be too loud.

Other problems were corrected, like the dullness in some records and magnetic tape, by using condenser microphones. This discovery came as a surprise in 1930. Turns out condenser mics have a natural boost in the midrange that canceled out the droop in that region on tape and records.

This discovery is what led to the use of pre-emphasis later, which is what the RIAA equalization is and is used for the exact same purposes – to correct problems associated with the recording medium and playback devices.

Pre-Emphasis in Recording & De-Emphasis in Playback

To make an extremely long story short, the National Association of Broadcasters (NAB) got sick of dealing with all of these various problems. Recordings from different countries, professional vs. amateur recordings, and recordings on various mediums all had different equalization characteristics.

The attempt to correct all of these problems on the fly was too troublesome so the NAB called for a standardization. Many were invented over the decades, like the RCA Victor New Orthophonic curve as an example, and were all pretty similar. Among these was the RIAA curve, which eventually won out.

The idea was always the same: to identify the problems heard during playback and either pre-emphasize or de-emphasize them during the printing of tape and records. They would either be corrected by an inverse EQ filter during amplification or corrected automatically by the characteristics of the recorded medium.

Ultimately the focus turned completely to standardizing a curve for vinyl records since they were the dominant recording medium for such a long period of time. That’s what led to the RIAA EQ curve.

RIAA Filter Standardization

Even after standardization was achieved, there were still tons of old records and even manufacturers using different curves. That’s why you see some old phono equalizers with switches to select different EQ curves like Columbia, CCIR, Decca, or TELDEC’s Direct Metal Mastering.

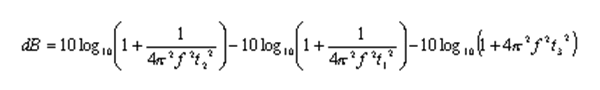

But most everyone adopted the RIAA’s recording curve and replay curve. There’s a complex mathematical equation used to generate the two curves (shown just above). The various standardization curves can be calculated using different time constant transition points, shown in the table below.

| RIAA | IEC | TELDEC | |

|---|---|---|---|

| t1 | 3180 μs (50 Hz) | 3180 μs (50 Hz) | 3180 μs (50 Hz) |

| t2 | 318 μs (500 Hz) | 450 μs (350 Hz) | 318 μs (500 Hz) |

| t3 | 75 μs (2122 Hz) | 50 μs (3183 Hz) | 50 μs (3183 Hz) |

These curves were limited to three transition points due to the inherent limitations in recording equipment and specifically in the cutting amplifiers used to apply the curve. They had their own upper limits so going higher than 3.2 kHz wasn’t needed.

The result is basically about a 20 decibel boost to the bass starting at 20 Hz and a 20 dB cut at 20 kHz. The various transition points define how the rest of the curve behaves, and are all very similar to one another.

The Enhanced RIAA EQ Curve

As time passed, more modern audio systems were invented that didn’t suffer from these bandwidth limitations. The manufacturers, recognizing the potential issue of boosting high frequencies indefinitely, added a high frequency roll-off above the highest frequencies human adults can hear (above 20 kHz).

This is good, although a bit extreme. Perhaps if they’d placed the roll-off just above 24 kHz there’d have been no pushback. But because 20 kHz is still below the upper limit of human hearing (especially in youth) at 24 kHz, people have sought to correct this with an additional 4th time constant a 7950 μs (20 kHz).

It was never standardized but has come to be known as the eRIAA, or enhanced RIAA curve. The International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC) and Telefunken and Decca (TELDEC/DIN), both seen in the table above, also have added the same 4th time constant.

RIAA Equalization in the Present

That catches us up to the present. The question obviously is “how does this effect us as musicians in the present?” There’s two main problems that you need to be aware of as a musician and one as a consumer (which is the same so won’t be mentioned).

All of these problems relate to people trying to use either the line input on their amplifier (instead of the phono input) or not using a turntable with an amplifier built in. Both of these scenarios mean you aren’t applying the RIAA curve!

Sending Vinyl Records to DJ’s

The first is kind of a passive problem, but one you want to know about even if you aren’t involved in the solution. Many electronic dance music artists and hip-hop artists still order vinyl records to send to DJ’s that spin live in the club or for DJ’s that still do record scratching / scrubbing.

Most of these DJ’s and turntablists that are worth their weight will be using professional turntables and phono amplifiers that correct for the RIAA playback curve. But there will be those that don’t. The manufacturers of the records you are purchasing will be applying the recording curve.

Any artists not using an amplifier with an RIAA equalizer in it will think something is wrong with your records, but they’ll likely have discovered this anyways using other records. It’s not a problem on your end, but one you should be aware of and ready to counter when someone makes false claims.

Sampling For Hip-Hop Production

In the same fashion above, you as a hip-hop beat producer that samples needs to be aware of the need to use a proper phono amplifier when sampling old records. As a beginner you may not even notice the problem or assume it’s normal and try to correct it with an EQ plugin later. This is bad.

You may think it’s beneficial to have the low-end gradually reduced in volume since you’ll be adding your own drums anyways, but you’ll also have the high-end boost, which will sound horrible. You can’t avoid using the correct amplifier anyways unless you purposefully intend on boosting a ton of noise in amplitude later.

The correct method will be to record from the turntable through the output of a phono amplifier (modern turntables may have one built in), and then EQ out the low-end yourself after the fact to make room for your new bass line and kick drum.

The RIAA Curve Still Matters!

This is a fairly interesting phenomenon that occurred in the past and since we’re back to idolizing records and turntables, it still matters even in the present. Especially considering so many artists are sampling old public license records and even those still under copyright.

If you’ve enjoyed this discussion, you’ll definitely like reading about the Fletcher Munson Curve, a similar EQ curve but one related to our ears themselves! All mixing engineers correct for it whether they realize it or not.

If you read this in earnest, it’s guaranteed you’ll remember it any time you deal with a record player, and you can tell your friends and family about it. They’ll find the RIAA curve an interesting topic of conversation.